Shared memory and consistency models

Mutual exclusion

Peterson algorithm

Originally syncs two threads, has been expanded to an arbitrary number of processes. However the size of the array is exponential to the number of processes.

Informally, consider the case where T1 enters the critical section. Then the loop condition must have been false, which means either flag2 was false or victim was set to 2. If flag2 was false, then T2 was not even trying to enter the critical section. If victim was set to 2, then T2 was trying to enter the critical section, but T1 won the race.

Code

//T1 T2

flag1 = true flag2 = true

victim = 1 victim = 2

while (flag2 && while (flag1 &&

victim == 1) { victim == 2) {

sleep();} sleep();}

// critical section // critical section

flag1 = false flag2 = false

Each thread begins by setting its flag to true. It then sets the victim variable to its thread id, and waits until either the other thread’s flag is false or victim is set by the other thread.

ELI5

Be a gentleman, let people go through the door before going yourself.

Lamport Bakery Algorithm

N-processes. Uses two shared variables, flag[2] and turn. Starvation-free.

- flag at 1 indicates that the process wants to enter the CS

- turn holds the id of the process whose turn it is

Code

// Init

choosing[1..n] = 0;

timestamp[1..n] = 0;

// Shared variables

bool boosing[n];

int timestamp[n];

// Entry CS Code

choosing[i] = 1;

timestamp[i] = 1 + max(timestamp);

choosing[i] = 0;

for (j = 1 to n) {

await(choosing[j]=0);

await(timestamp[j] == 0) or (timestamp[i] < timestamp[j]);

// Exit CS Code

timestamp[i]=0

}

Linearizibility

For any concurrent execution, there is a total order of the operations such that each read to a location (variable) returns the value written by the last write to this location (variable) that precedes in the ordered. Total order.

Other more relaxed models exist

- sequential

- causal

- PRAM

- weak, etc…

Specs

- The total order must be consistent with the temporal order of operations

- Each operation op(Read or Write) has an invocation and response events

An execution in global time is viewed as sequence seq of such invocations and responses

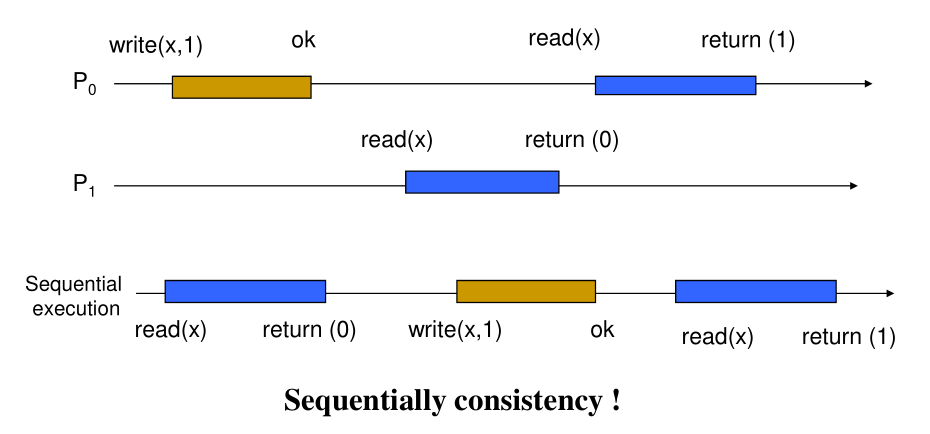

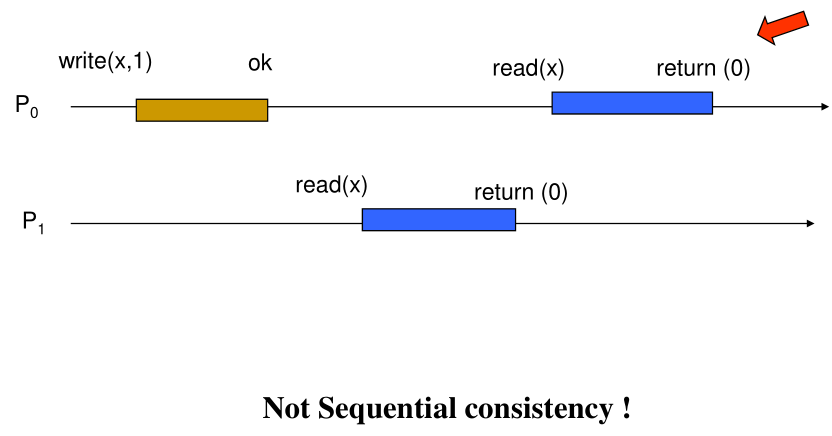

Sequential

- The result of any execution is the same as if all operations of the processors were executed in some sequential order

- The operation of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the local program order

- Any interleaving of the operations from the different processes is possible. But all processors must see the same interleaving.

- Even if two operations from different processes (on the same or different variables) do not overlap in a global time scale, they may appear in reverse order in the common sequential order seen by all

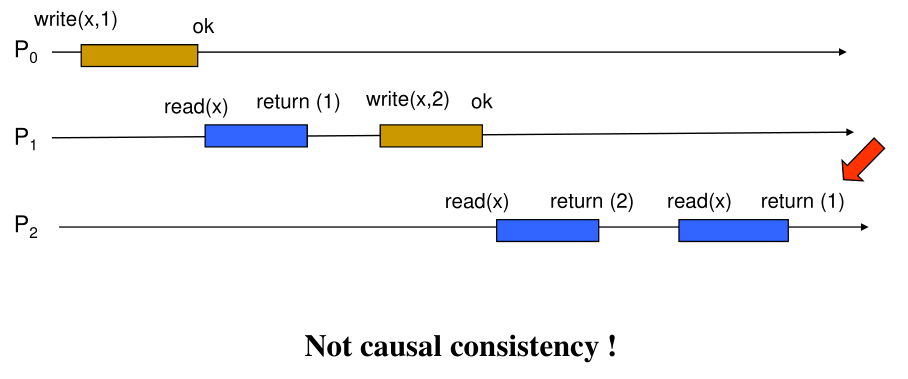

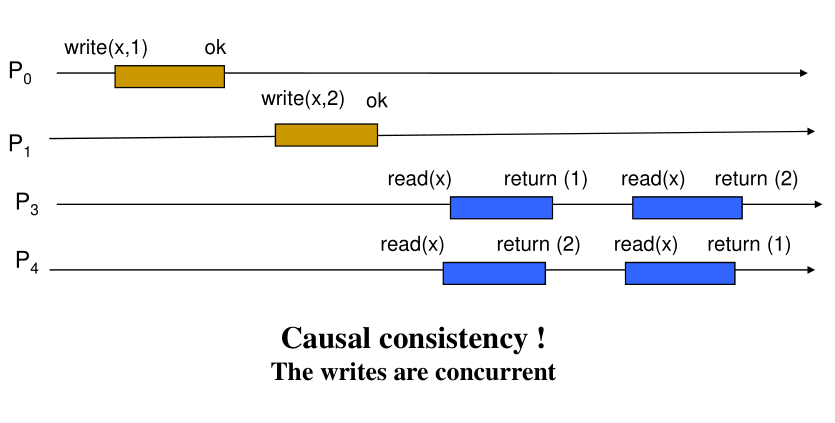

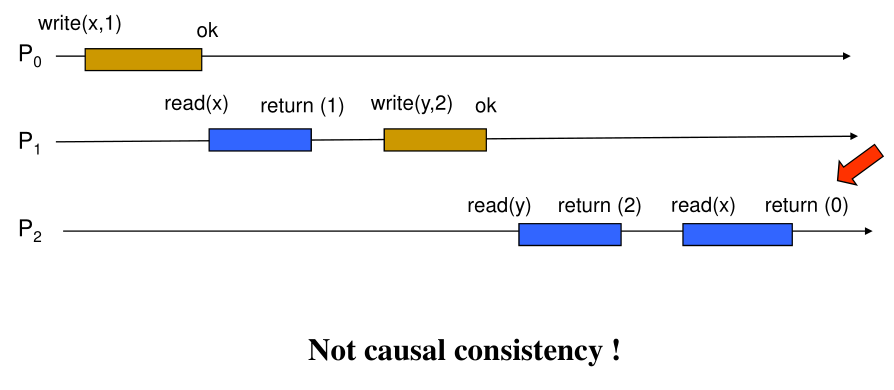

Causal

Causal relation is:

- Local order of events of a process define local causal order

- A

writeoperation causally precedes areadoperation of another process if thereadreturns the value written by thewriteoperation - The transitive operation of the baove two relations defines the global causal order

And then:

- Only

writesthat arecausally relatedmust be seen by all processes in the same order. Concurrent writes must be seen in a different order.

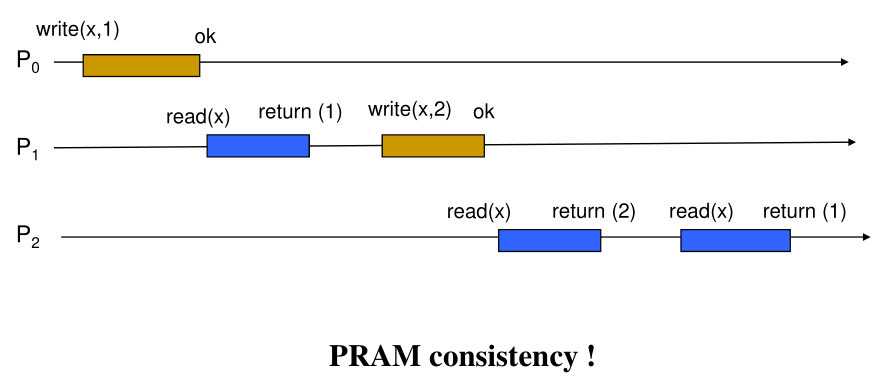

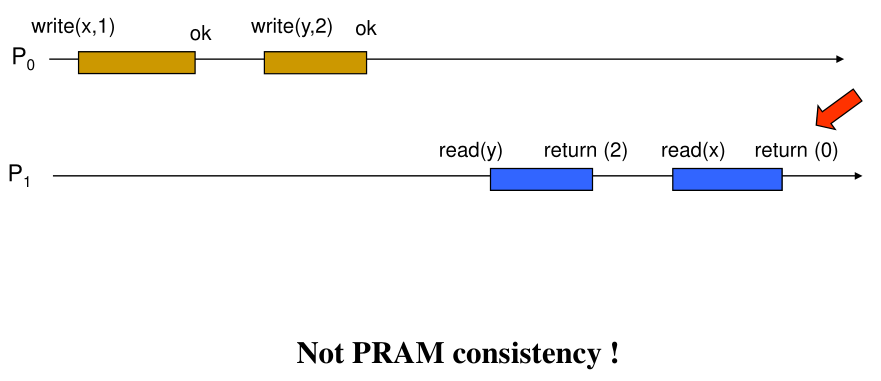

PRam

Writes done by a single processor are received by all other processes in the order in which they were issued but writes from different processes may be seen in a different order by different processes

- Only the local causality relation needs to be seen by other processes

- Writes from the same process must be seen b the others in order they were issued

Registers

Abstraction of distributed shared memory by Lamport

Safe register

- Read does not overlap with a write Read returns the most recently written value

- Read overlaps with a write Read returns any value that the register could possibly have

Regular register

It is a safe register and:

- if Read overlaps with a write then read returns either the most recent value of a concurrently written value

Atomic register

is regular and

- read and write that overlap are linearizable. There exists an equivalent totally ordered sequentilal execution of them

TD

1.1 Est-ce que la variable timestamp est bornée? Justifiez

Non borne. Si les processus reviennent on est pas oblige de retourner a 0

1.X Deux processus I et j peuvent avoir le timestamp: timestamp[i]=timestamp[j]. En se basant sur le code de la fonction max ci dessus expliquez comment cette égalité peut arriver. Est-t-elle un problème? Justifier.

C’est pas atomique, on peut se retrouver dans la même instruction. Entre SC n’est pas protégée contre plusieurs accès concurrents alors entre 2 instructions on se retrouve avec 2 processus -> même timestamp à la fin / non c’est pas un problème car L6 comparaison entre les indices

1.2 En donnant un scenario d’exécution, expliquez pourquoi l’implémentation ci-dessus de la fonction max toute seule n’assure pas la sureté de l’algorithme de la boulangerie?

P1 P2 P3

- Timestamp[2] = timestamp[3]=1

- P2 et SC (phase 3)

- P3 attend entre SC (Phase 2)

- P1 exécute la Phase 1 jusque la ligne 4 de fonction max k=2

- P2 sort SC -> timestamp[2] = 0 (phrase 4)

- P3 rentre en SC

- P1 finit phase 1 / ligne 5 / timestamp[1]=1

- P1 phase 2 (compare timestamp[1] et timestamp[3] =? Entre en SC

Deux processus peuvent avoir la même valeur du timestamp.

1.3 Corrigez l’algorithme

max () {

int MAX=0;

int TEMP=0;

for j=1 to N {

TEMP=timestamp[j];

if (MAX < TEMP)

MAX=TEMP;

}

timestamp[i] = 1+MAX;

}

1.4 Est-ce que les phrases sont-elles vraies? Justifiez votre réponse.

1 Vraie 2 Non, ts[i]=ts[k] avec i<k

1.5 Pourquoi l’algorithme de la boulangerie a-t-il besoin du tableau choosing? Quel problème entrainerait l’élimination de la ligne 5 (boucle d’attente sur la variable choosing de l’algorithme)?

Pour des raisons de sureté attendre le choix du TS après le comp. C’est une sorte de section critique, barrière en C, bla.

i exécute Ph1 sort avec ts=1

K vient de rentrer en ph1, donc ts[k]=0

i va en ph2 et ph3 donc en SC

K reprend la main - son ts[k] avec le max =1, il arrive en ph2, ts[k]=ts[i], et k<i donc aussi SC.

1.6 Donnez le code d’un tel algorithme

(1.7/2017, I guess)

Read-modify-write

register int ticket = 0;

register int valid = 0;

int ticket_i

inc(register r) {

r +=1

}

Enter SC:

ticket i = read-modify-write(ticket, int);

while (ticket_i != valid);

Exit SC:

read-modify-write(valid, int)

1.7

read_modify_write

register int ticket = 0;

register int valid = 0;

inc (register r) {

r = (r+1)%n

}

int ticket i;

EntrySC:

ticket i = read_modify_write(ticket, inc);

while(ticket i != valid);

ExitSC:

read_modify_write(valid, inc);

1.8

register int ticket = 0;

atomic bit valid[N] (valid[0] = 1; valid[2..N-1] = 0);

EntrySC:

ticket_i = read_modify_write(ticket_i, inc);

while (valid[ticket_i] != 1);

ExitSC:

valid[ticket_i] = 0;

valid[(ticket_i+1)%N] = 1;

Exercice 1.9

On a ticket = 0 et valid = [1 0 0 0]

Proc_i: EntrySC

ticket_i = 0

ticket_j = 1

ticket = 2

valid = [1 0 0 0]

Proc_i: ExitSC

ticket = 2

valid = [0 1 0 0]

Proc_j: EntrySC

Proc_j: ExitSC

ticket = 2

valid = [0 0 1 0]

Exercice 2

| Step | Safe | Regular | Regular |

|---|---|---|---|

| P0write | (R’,0) | (R’,1) | (R’,0) |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P1read | R’{0,1} | R{0,1} | R{0} |

boo WRSW safe register R'= 0;

boo previous = 0;

write (R,val) {/* P0 */

if(previous != val){

R'=val;

previous = val;

}

return OK;

}

bool Read(R){

val = R';

return(val);

}

2.1 Quel modele de coherence?

// TODO: Add image

Pas de overlap entre p2.write(x,3) et p3.read(x)

- pas strict

// TODO: Why? - sequentiel oui, c’est possible de trouver une sequence qui est valable

Sequence possible:p2.write(x, 1), p1.read(x)=1, p1.write(y,2), p3.write(y,4), p2.read(x)=1, p1.read(y)=4, p2.write(x, 3)

2.2 Writes causally related

write(x, 1) -> write(x, 3)

write(x, 1) -> write(y, 2)

write(x, 3) -> write(y, 4)

Par transitivite:

write(x, 1) -> write(y, 4)

2.3 Sequential? Causal? PRAM?

Causal : les operations d’ecriture liees causalement sont vues dans le meme ordre par tous les processus

Causal implique PRAM

Pas de coherence sequentielle, contre-exemple:

p2: w(y, 2), r(y)=4

p3: w(y, 4), r(y)=2

2.4 Sequential au lieu de linearizability

Voir schema Linearizibility slide 14 - modele sequentiel

Pas strict, car pas de overlap entre p1.write(x, 1) et p2.read(x)=0

int x;

upon operation(op, val)

if(op==write)

total_order_broadcast(op, id_i);

else

return x;

upon deliver of messages<write, val, id>

x = val;

if (id = id_i)

return ok;

// TODO Elle a reecrit la meme chose que sur le poly?